On the A line of the RER in Paris last weekend, we spotted a chap wearing a black t-shirt. The design was simple: in all white lines, a man cowered in a battery cage, stretching his arm between the bars to slot a piece of paper into a small box which squatted on the roof of the cell. Above were the words, “Le droit de vote.” Below, “Le droit de choisir votre maître.”

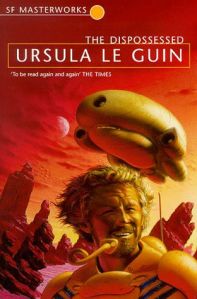

Also that weekend, I was reading Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed. A friend (hi, Aileen!) thrust this book into my hands at the very moment she learned I hadn’t previously read it. The fairly bald piece of polemic stamped on that Parisian’s shirt got me thinking about the far subtler politics of the novel in my bag. The protagonist is Shevek, a brilliant physicist forced from his anarchist homeworld of Anarres to the capitalist hegemony of its sister planet, Urras, from which his ancestors fled centuries ago, inspired by the writings of the syndicalist philosopher, Odo. “Our men and women are free – possessing nothing, they are free,” he insists at an Urrastian party. “And you the possessers are possessed. You are all in jail. Each alone, solitary, with a heap of what he owns. You live in prison, die in prison. It is all I can see in your eyes – the wall, the wall!” [Gollancz SF Masteworks edition, 2002, pg. 199]

The Dispossessed famously opens with a wall, the one built around the space port of Anarres by the planet’s inhabitants, to keep out the pollutants of their corrupt, market-driven cousins. And yet, of course, that same wall locks the Anarresti in. The subtitle of The Dispossessed has come to be accepted, following the lionising of a particular piece of first edition blurb, as ‘An Ambiguous Utopia’. But there are at least two propblems with this appelation: one, there is clearly more than one utopia in the novel; and, two, there is no ambiguity attempted, at least not when reading the novel today. If the Le Guin of 1974 was attempting to posit a hippie-feminist commune in space which nevertheless felt real, time has yet further worn away those ideals. But it seems to me that her approach was never so simplistic: late in the novel, the Terran ambassador to Urras paints that planet as a paradise. “I know it’s full of evils,” she admits, “full of human injustice, greed, folly, waste. But it is also full of good, of beauty, of vitality, achievement. It is what a world should be! It is alive, tremendously alive – alive, despite all its evils, with hope. Is that not true?” [pg. 286]

Shevek can do nothing but nod – all of that is true. And Le Guin’s Terran ambassador, from an Earth ruined and defoliated, full of plastic detritus and wasted potential, also gave me pause. Her objection to the harsh, bureaucratic, joyless life of the Anarresti anarchist – all allocated labour and scarce rations – is also mine: that it is not enough merely to abolish property; to liberate a people truly is to release in them the capacity to be happy, to lust for life and exhibit hope. The Odonian solution – to abolish property, centralisation and the state – is also the removal of much of that which can alleviate suffering both in real ways (the state can interfere, it can level) and in transitory ways (property can console and, yes, divert). On Anarres – and Le Guin deals with this in some of her most fascinating passages in the novel – even love and romance is a brutal sort of occupation. In The Dispossessed, unalloyed anarchism is, as much as unalloyed capitalism, the removal of all that can comfort, console and calibrate.

And so the wall. By adopting an option or approach, we risk locking out the benefits of the alternatives. By isolating ourselves in our own pursuits, as Shevek does, we refuse the ability of others to help us; by pooling ourselves into a collective, as the faceless masses of the Urrastian communist utopia of Thu do, we render our lives featureless and flattened. And yet in the capitalist superpower of A-Io, there are everywhere Urrastians ready to overthrow their system, which rewards the already privileged – the rich, men – and marginalises the perennially vulnerable – the poor, women. The great trick of The Dispossessed is that none of these perfected systems (and what is fascinating about Le Guin’s political systems is their purity – so its capitalism is not governed by social democracy, its communism would not be recognised by modern day China) are presented as ambiguous. There is something unambiguosly wrong with all of them.

No coincidence, then, that Shevek’s great contribution to physics is the Theory of Simultaneity, a conception of space-time which enables instantaneous communication across the stars. All things, all moments, exist at once, in a kind of balance. So, too, all systems of government? Indeed, if anything in the novel is treated by its characters as a pipe dream, a myth, an unlikely utopia, it is a world of simultaneity: “Simultaneity!” scoffs Sabul, Shevek’s mentor at Abbenay University, upon their first meeting. “What kind of profiteering crap is Mitis feeding you up there?” [pg. 89] In part, Shevek’s brilliance is in this way rejected by his levelling society – don’t eogize, he is constantly told – whilst Urras embraces the concept. This is the reason for Shevek’s journey from Anarres to Urras and back again.

But the Urrastian inability to conceive of the unifying potential of the Theory – their need to profit from it and conquer with it – is as much a rejection of its truth as the Anarresti jealousy. The Theory of Simultaneity is the only real tool in the novel which has a chance of knocking down the walls and bridging the gulfs between the competing, but equally corrupting, conceited governing systems. It is the utopia; Shevek’s heroism is in remaining true to that ideal, rather than any single political creed.

A truly wonderful work….

However, her other Hugo winning work, ‘The Left Hand of Darkness’ is FAR superior (in my opinion — hehe).

Check it out if you haven’t! If you love this one you’ll enjoy ‘The Left Hand…’